Bedside Clinical Question:

How to interpret elevated PT/INR/PTT levels in patients on DOAC's and do we need reverse the patient based on elevated levels?

Background:

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)—including apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and dabigatran—are increasingly favored over warfarin due to fixed dosing, no need for routine INR checks, and fewer drug-drug and drug-food interactions, while maintaining high clinical efficacy.

Dabigatran is a direct thrombin (Factor IIa) inhibitor, while apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban are Factor Xa inhibitors.

Ideally, DOAC activity should be assessed using specific anti–Factor IIa or anti–Factor Xa chromogenic assays, but these are often unavailable in routine clinical practice.

Managing DOAC-related bleeding involves agent-specific reversal when possible. Idarucizumab is indicated for dabigatran, and andexanet alfa for apixaban and rivaroxaban. When unavailable, PCC, aPCC, or FFP may be used as non-specific reversal options.

At CCH-Stroger hospital, we have FFP, FEIBA (aPCC), and idarucizumab (restricted). Andexanet alfa is non-formulary.

In our patient population, rivaroxaban and apixaban (Factor Xa inhibitors) are the most commonly prescribed agents and therefore will be the primary focus of this discussion below.

Answer

DOACs cannot be reliably monitored by PT/INR/PTT because they work differently and don’t affect the INR in a consistent or predictable way.

Factor Xa inhibitors are monitored using anti-Xa activity assays tailored to the specific drug.

Clinical context such as renal/hepatic function, drug interactions, timing of last dose is also essential for interpreting coagulation results in DOAC-treated patients, and routine measurement of DOAC plasma concentrations is not indicated. There is limited availability of standardized, DOAC-specific assays in the U.S., and the minimum DOAC level associated with bleeding risk is not well established.

Therefore, the decision to reverse should be based on signs/ symptoms rather than coagulation levels.

Consider reversal for:

Fatal bleeding and/or

Symptomatic bleeding in critical areas (e.g., brain, spine, eye, retroperitoneal, joints, pericardium, muscles with compartment syndrome) and/or

Bleeding causing hemoglobin drop ≥2 g/dL or requiring ≥2 units blood transfusion

Conclusion

In the absence of reliable drug-specific assays, DOAC reversal should be guided by clinical severity—not typical coagulation labs like PT, PTT, or INR—especially in life-threatening or critical-site bleeding.

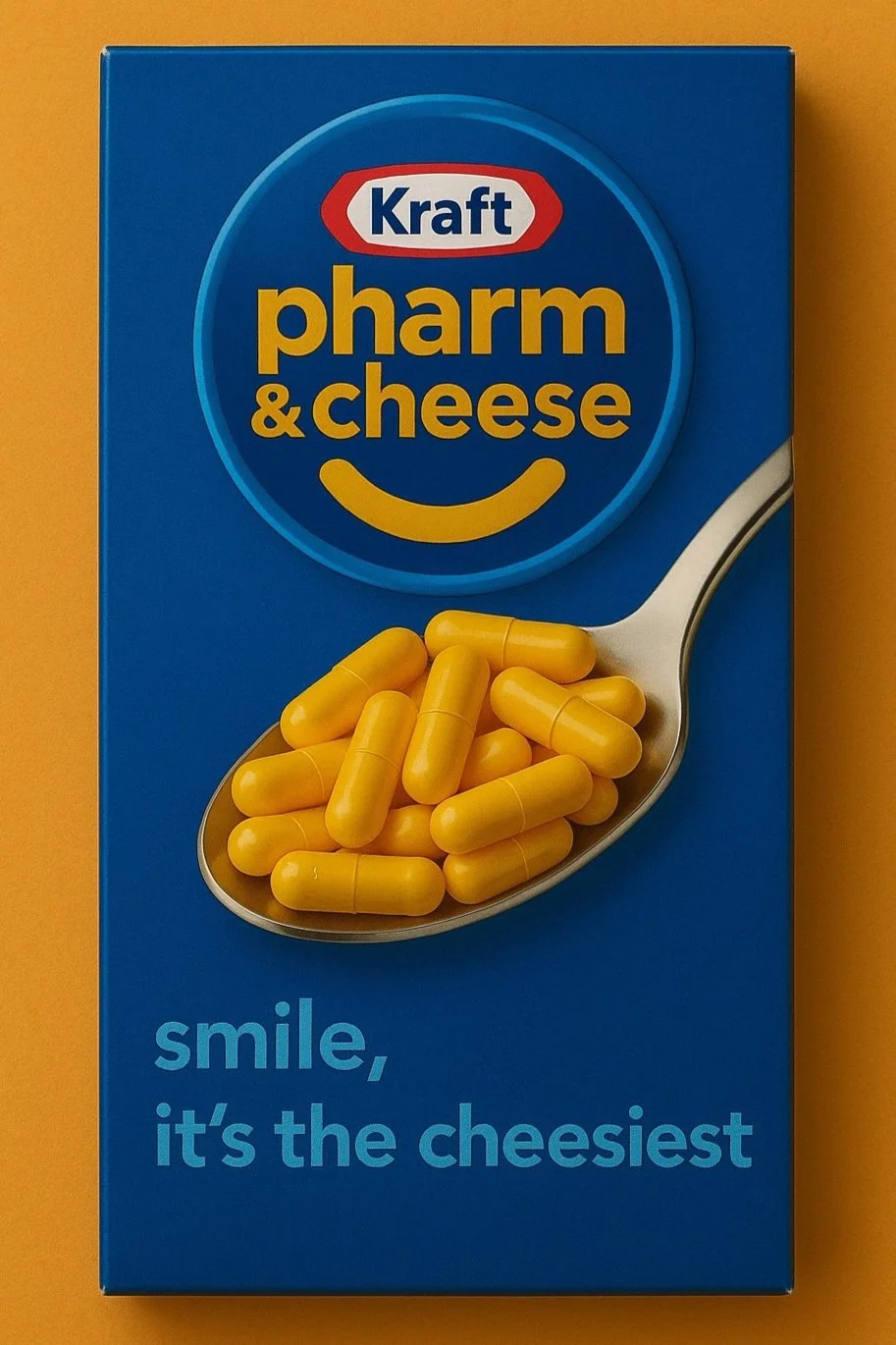

Authored By Alejandra Alvarez, PharmD & Joanne C. Routsolias, PharmD

References

Shah SB, Pahade A, Chawla R. Novel reversal agents and laboratory evaluation for direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOAC): An update. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63(3):169-181.

Crowther M, Cuker A. How can we reverse bleeding in patients on direct oral anticoagulants?. Kardiol Pol. 2019;77(1):3-11.

Moia M, Squizzato A. Reversal agents for oral anticoagulant-associated major or life-threatening bleeding [published correction appears in Intern Emerg Med. 2020 Jun;15(4):737. doi: 10.1007/s11739-019-02232-y.]. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14(8):1233-1239. doi:10.1007/s11739-019-02177-2.

Samuelson BT, Cuker A, Siegal DM, Crowther M, Garcia DA. Laboratory Assessment of the Anticoagulant Activity of Direct Oral Anticoagulants: A Systematic Review. Chest. 2017 Jan;151(1):127-138.

Dunois C. Laboratory Monitoring of Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs). Biomedicines. 2021 Apr 21;9(5):445. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9050445. PMID: 33919121; PMCID: PMC8143174.