The patient is a 69-year-old female with past medical history of remote myocardial infarction status post stent placement 19 years ago, who is presenting for concern of chest pain. She states the pain started approximately 30 minutes prior to arrival and has shortness of breath as well as chest pressure. The pain radiates down her left arm. The vital signs are as follows:

HR: 200, BP: 118/91, RR: 20, O2: 95% on RA

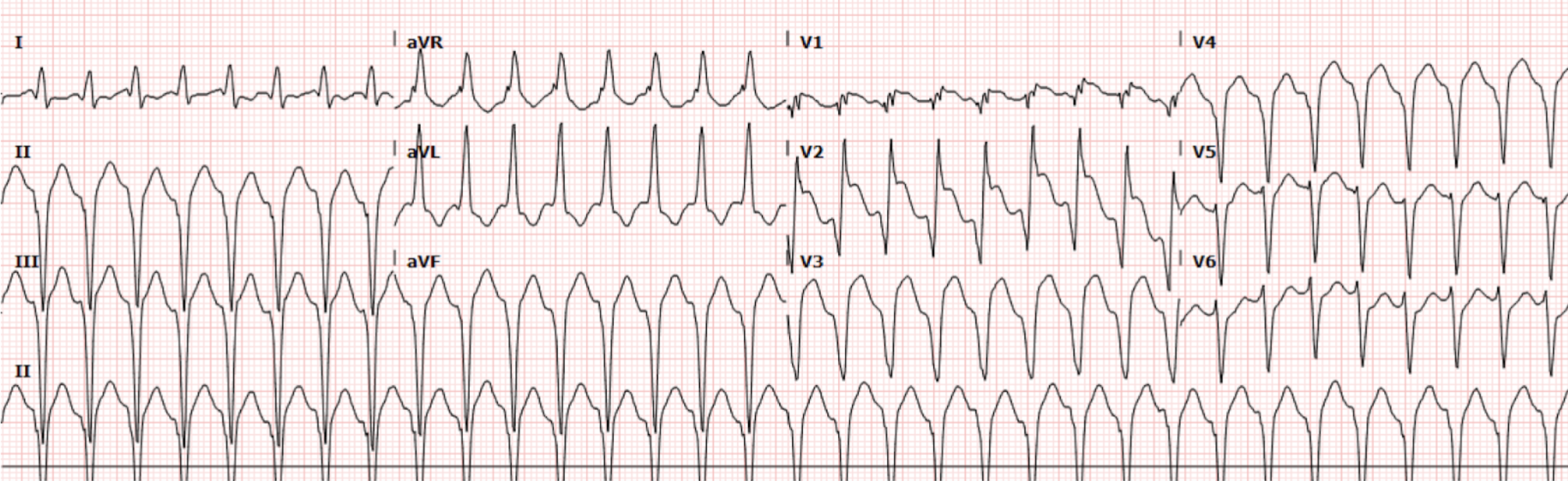

The patient was immediately placed in a resuscitation bay and noted to have a wide complex tachycardia on the monitor. An EKG (Figure 1) was obtained and shows the following:

Interpretation: Rate: 200 bpm; Rhythm: regular; Axis: left axis deviation (I: pos., II: neg., aVF: neg) Intervals: PR: n/a; QRS: 120, prolonged; QT: 260, normal; P-Waves: buried; QRS Complex: wide, predominantly negative complexes; ST Segment/T-waves: abnormal appearing T-Waves, discordant with QRS complex

Based on the EKG findings above, this patient was noted to be in ventricular tachycardia (VT) and cardiology was immediately called to the bedside. Amiodarone 150mg was trialed twice with no conversion. Afterwards, the patient was started on empiric magnesium therapy and an Amiodarone drip. Lidocaine was trialed as well, with no relief. Finally, the patient was electrically cardioverted and the following EKG (Figure 2) was obtained:

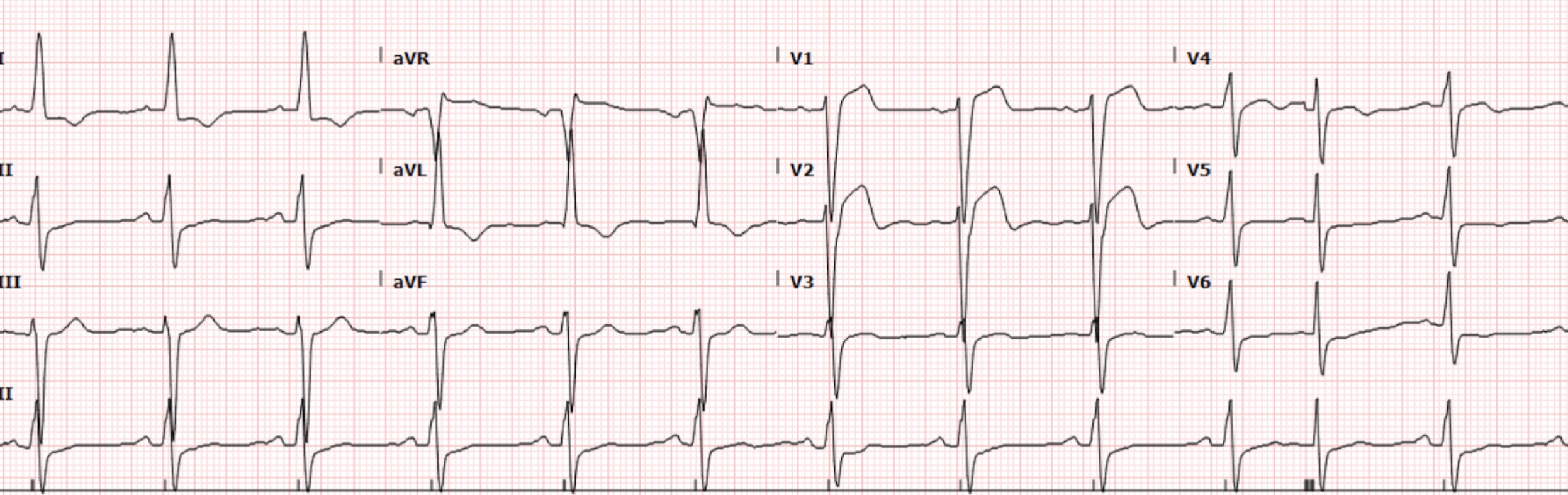

Figure 2. EKG after cardioversion

Interpretation: Rate: 73 bpm; Rhythm: regular; Axis: left axis deviation (I: pos., II: neg., aVF: neg) Intervals: PR: 180, normal; QRS: 128, prolonged; QT: 362, normal; P-Waves: normal; QRS Complex: wide, normal progression; ST Segment/T-waves: ST elevation in V1, V2, V3, reciprocal depression in II, V6.

This patient was taken to the cath lab directly following cardioversion for concern of the acute ST segment elevation on the EKG in Figure 2. During the procedure, she was noted to have persistent coronary artery disease, without any acute obstructive lesions. While in the CCU, the patient had a TTE that showed a left atrial aneurysm with scarring in the LAD territory, consistent with ischemic cardiomyopathy. This is thought to be the cause of ST elevation in the anterior leads. This patient had multiple follow-up EKGs during her stay in the CCU, all of which showed persistently elevated ST segments. The patient underwent ICD placement over this admission and was doing well on outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

On arrival to the emergency department, this patient was immediately noted to have a regular wide-complex tachycardia (WCT) with a rate of 200. The differential for this type of rhythm includes the following:

Ventricular Tachycardia

SVT with aberrancy

While it can be difficult to establish the difference between these types of tachyarrhythmias, it is important to remember that in over 80% of cases, the diagnosis is going to be VT. There are aspects of this patient’s history and EKG findings in this case that point towards a diagnosis of VT. Some factors that may increase a patient’s risk of VT include age greater than 35, history of previously diagnosed CAD, and ischemic or structural heart disease (which this patient was later diagnosed with on echo). There are additionally some EKG findings that increase the likelihood that the patient is experiencing VT.

EKG features suggestive of VT over other etiologies of wide complex tachycardia’s include:

Absence of stigmata of RBBB or LBBB morphology

Very prolonged QRS complexes (>160)

Anterior leads showing an RSR’ where the R is taller than the R’ (most specific finding for VT)

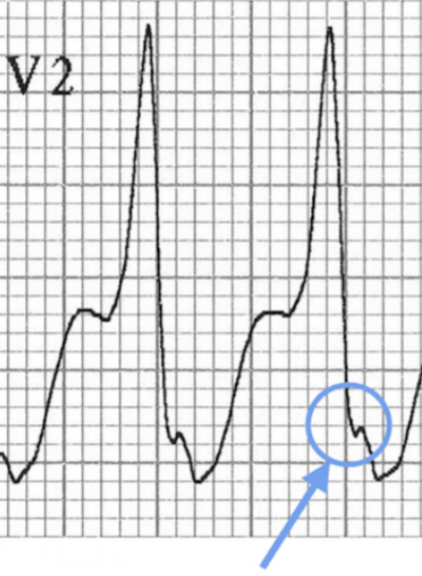

Josephson Sign: notching near the end of the S wave (Figure 3)

Figure 3. Josephson sign (Figure adapted from: https://litfl.com/vt-versus-svt-ecg-library/)

Additionally, there are factors that may point you away from a diagnosis of VT. In patients with a history of RBBB/LBBB or other paroxysmal tachyarrhythmias, there should be a higher suspicion for possible SVT with aberrancy or other WCT. Specifically, for patients on flecainide, there is an increased likelihood of SVT with aberrancy that can present very similarly to VT. There are multiple other diagnostic algorithms that may be used to determine the rhythm, such as the Brugada Criteria and the Vereckei Algorithm, however none of them are absolute. For more discussion on the differentiation between VT and SVT with aberrancy, this Life in the Fast Lane webpage article linked here is an excellent resource: https://litfl.com/vt-versus-svt-ecg-library/

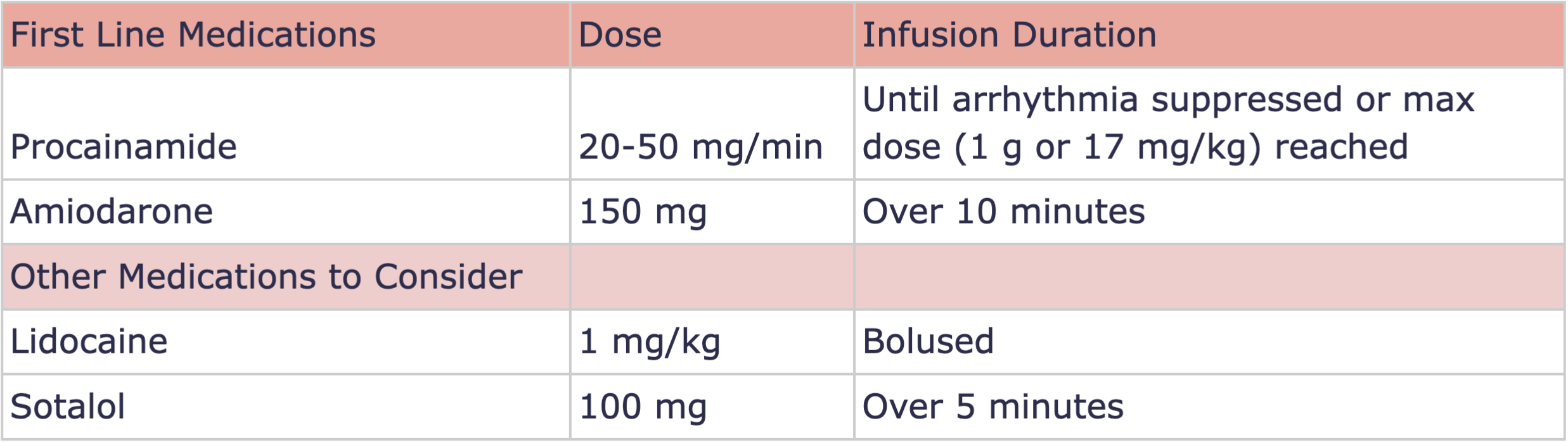

Ultimately, these tachyarrhythmias may be impossible to differentiate from each other with just an EKG and may require more invasive diagnostic techniques. Luckily, for an unstable patient in acute distress, regardless of the rhythm, the treatment will always remain the same: synchronized cardioversion. For the case above, the patient was noted to have stable vital signs, so multiple different medications were trialed in an attempt to chemically cardiovert her. In addition to those used above, there are many other medications that may be used to convert VT to a normal rhythm. Below is a summary of some of the mainstays of treatment for a stable patient in VT.

Table 1. Treatment options for stable ventricular tachycardia

In the case above, the lidocaine and amiodarone were preferentially chosen as they were readily available at the bedside directly from the crash cart. The cardiac arrest dosages were adapted for use in this stable patient.

After stabilization, these patients will require admission, likely to an intensive care setting for further work-up and management. For our patient, she went directly to the cath lab followed by a stay in the CCU. The cause of her VT episode was likely related to the ischemic cardiomyopathy found on her TTE and she now has an ICD to prevent further episodes.

Take-away Points:

Wide Complex Tachycardias may be difficult to differentiate from each other, however, in an unstable patient the treatment will always be synchronized cardioversion

If you are uncertain of the rhythm, and the patient is stable, take an extra minute to review the EKG for the findings above to help differentiate VT:

Absence of RBBB or LBBB morphology

Very prolonged QRS complexes (>160)

An RSR’ with R > R’

Josephson Sign

Key points in patient history can help sway you towards a diagnosis of VT, such as history of ischemic disease and known structural abnormalities

Procainamide and Amiodarone are generally considered the treatments of choice for stable VTach, but if you are in a pinch, use what you have in the crash cart at the bedside

References:

Burns, Ed. Buttner, R. VT vs SVT. Life in the Fast Lane. October 8, 2024. https://litfl.com/vt-versus-svt-ecg-library/

Burns, Ed. Buttner, R. Ventricular Tachycardia - Monomorphic VT. Life in the Fast Lane. October 8, 2024. https://litfl.com/ventricular-tachycardia-monomorphic-ecg-library/

Foth C, Gangwani MK, Ahmed I, et al. Ventricular Tachycardia. [Updated 2023 Jul 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532954/

Ezeh E, Perdoncin M, Moroi MK, Amro M, Ruzieh M, Okhumale PI. The Slower, the Better: Wide Complex Tachycardia Triggered by Flecainide in an Elderly Female. Case Rep Cardiol. 2022 Oct 15;2022:1409498. doi: 10.1155/2022/1409498. PMID: 36284751; PMCID: PMC9588376.

Authored by Erica Dolph MD and Ari Edelheit MD