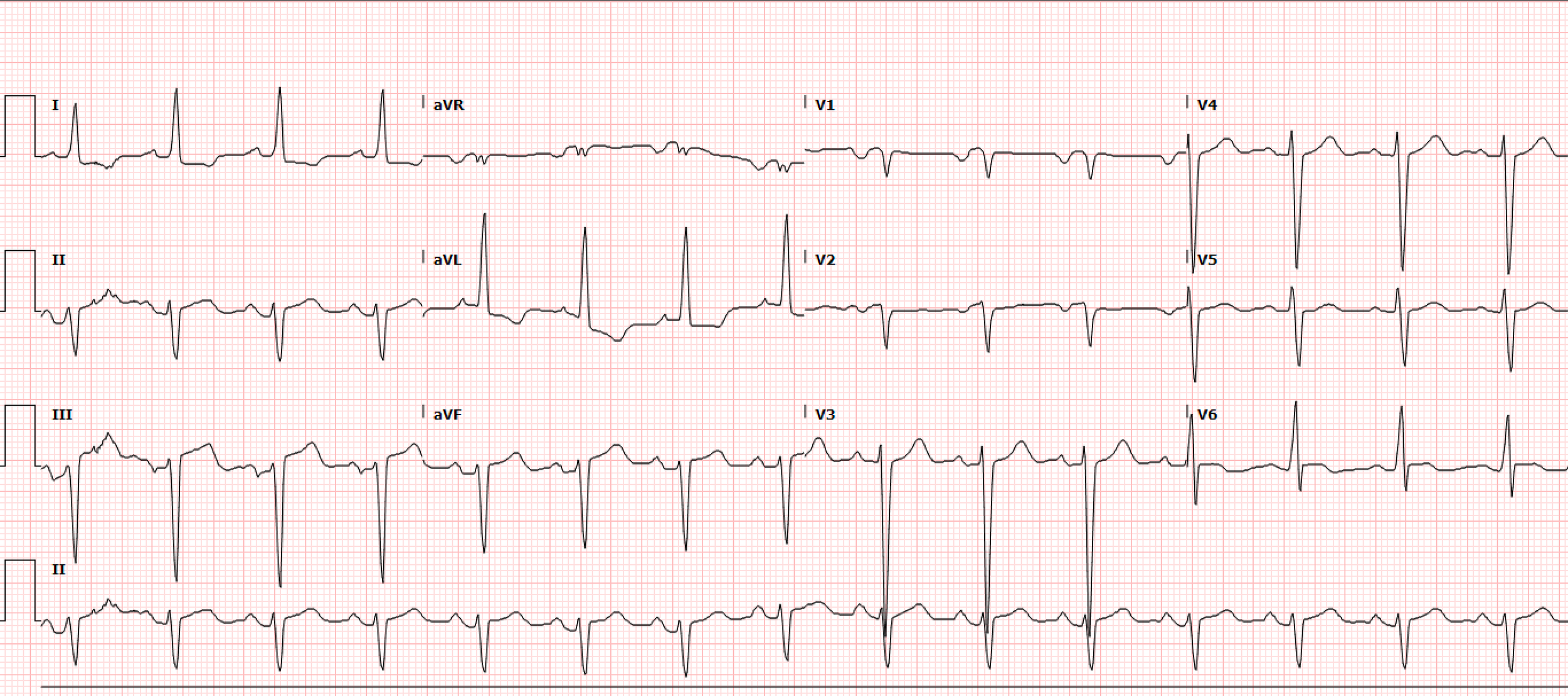

A 34-year-old male with a history of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction of 20-25%, hypertension, and cocaine use disorder presented to the emergency department with leg swelling, cough with bloody sputum, and chest pain on exertion. A triage EKG is obtained prior to rooming in the resuscitation bay (Figure 1).

Interpretation: Rate: 89 bpm; Rhythm: regular rhythm; Axis: left axis deviation (I: pos., II: neg., aVF: neg) Intervals: PR: 169, normal; QRS: 112, normal; QTc: 431, normal; P-Waves: present, upright; QRS Complex: normal, good R wave progression; ST Segment/T-waves: 1mV STE in lead II, 1.5mV ST elevations in leads III, aVF with reciprocal 1.5mV ST depressions in lead I, aVL and 0.5mV in V2

A repeat EKG showed no interval change in the above ST abnormalities. The initial troponin was 1.06ng/mL and the two-hour troponin was 39.41 ng/mL which prompted an urgent Cardiology consult. A CTPE was obtained which demonstrated an acute pulmonary emboli in the segmental and subsegmental branches of the right middle lobe with associated pulmonary infarct/hemorrhage without right heart strain. A repeat troponin at this time was 45ng/mL. Due to the lack of evidence of right heart strain, the EKG findings in combination with the rising troponin, prompted a formal TTE to evaluate for myocardial injury patterns.

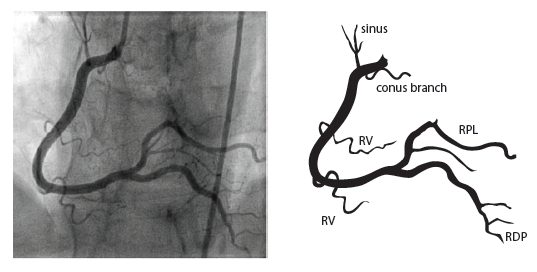

The formal TTE demonstrated a probable apical LV thrombus measuring ~1.5 cm (L) x 1.3 cm and a regional wall motion abnormality (RWMA) with akinesis of the basal inferoseptal and basal mid-inferior myocardium. Note, this RWMA correlates with the EKG findings of STE in the inferior leads II, III, aVF with reciprocal changes in I, aVL and V2. This then prompted a left heart catheterization which demonstrated cut-off of the distal inferior branches of the right posterolateral artery (RPL) which suggests embolism. Note, the anatomic location of this embolism correlates with the echo RWMA and the EKG findings of STE in the inferior leads II, III, aVF with reciprocal changes in I, aVL, V2 (Figure 2). Specifically, the occluded posterior artery is represented on the EKG by the ST depression in V2.

Figure 2. Coronary Anatomy (Image from: https://www.pcipedia.org/wiki/Coronary_anatomy)

The patient was started on aspirin for the coronary embolism which cardiology attributed to the myocardial injury, EKG findings, and troponin elevation. The patient ultimately did well and was discharged from the CCU to home.

Discussion

Coronary embolism is a rare and likely under-recognized cause of myocardial injury and infarction most commonly caused by infective endocarditis (22.4%), atrial fibrillation (17.0%), and prosthetic heart valve thrombosis (16.3%) [1]. A retrospective analysis attributed up to 3% of ACS events to coronary embolism [2].

There are three categories of coronary emboli: direct, paradoxical, and iatrogenic. Direct coronary emboli result from thrombi of the left atrium, left ventricle, or pulmonary veins, endocarditis, or cardiac tumors. Paradoxical coronary emboli result from thrombi in the deep venous system traveling through a PFO or ASD into circulation. Iatrogenic coronary emboli result when clot from suboptimally heparinized instruments or calcific material from valves or the coronary arteries break off and lodge in the coronaries [3].

Proposed Scoring System for Definite (2 or more major criteria, 1 major and 2 minor, or 3 minor criteria) and Probable Coronary Embolus (1 major and 1 minor or 2 minor criteria) were developed by Shibata et al. and are as follows:

Major Criteria:

Angiographic evidence of coronary embolus/thrombus (e.g., a filling defect, or abrupt occlusion in an artery without significant atherosclerosis)

Concomitant coronary emboli in multiple coronary vascular territories

Concomitant systemic embolization without left ventricular thrombus attributable to acute myocardial infarction

Histological evidence of venous origin of coronary embolic material

Evidence of an embolic source based on TTE, TEE, CT, or MRI (e.g., clot in left atrial appendage)

Minor Criteria

<25% stenosis on angiography in the nonculprit vessels

Atrial fibrillation

Presence of embolic risk factors, cardiomyopathy, rheumatic heart disease, prosthetic valve, PFO, ASD, history of cardiac surgery, infective endocarditis, or hypercoagulable state [3].

According to the above criteria, the patient in this case would fall under definitive coronary embolism by two major criteria of (1) angiographic evidence of coronary embolus and (2) evidence of an embolic source based on TTE. However, had this patient presented to a center without cardiac catheterization ability, the patient still can be diagnosed with probable coronary embolism with these criteria by 1 major and 1 minor (1) Evidence of an embolic source based on TTE and (1) presence of embolic risk factors, cardiomyopathy, rheumatic heart disease, prosthetic valve, PFO, ASD, history of cardiac surgery, infective endocarditis, or hypercoagulable state.

Ultrasound Spotlight: Remember to consider severe heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in your differential for thromboembolic risk. The recent July 2025 Ultrasound of the Month highlighted a case that demonstrated spontaneous echo contrast (SEC) or echocardiographic smoke. This finding is indicative of the aggregation of blood components in stasis or low-flow states that can develop into cardiac thrombi.

Take Away Points

ST elevation in the inferior leads is highly suspicious for OMI when paired with reciprocal changes in I, aVL. This is almost assuredly an inferior OMI when also paired with ST depression in V2.

Don’t forget to think of coronary embolism when a patient with thromboembolic risk factors presents with subtle EKG findings and an elevated troponin

Correct diagnosis of coronary embolism could change patient management: oral anticoagulation for CE versus traditional DAPT in ACS

Remember that not all clinically significant myocardial injury meets STEMI criteria, this case is better described by the OMI/NOMI definition with the <2mm STE and STD in the index EKG

References

Lacey MJ, Raza S, Rehman H, Puri R, Bhatt DL, Kalra A. Coronary Embolism: A Systematic Review. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21(3):367-374. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2019.05.012

Shibata T, Kawakami S, Noguchi T, et al. Prevalence, Clinical Features, and Prognosis of Acute Myocardial Infarction Attributable to Coronary Artery Embolism. Circulation. 2015;132(4):241-250. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.015134

Raphael CE, Heit JA, Reeder GS, et al. Coronary Embolus: An Underappreciated Cause of Acute Coronary Syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(2):172-180. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2017.08.057

Siddiqui MA, Holmberg MJ, Khan IA. Spontaneous echo contrast in left atrial appendage during sinus rhythm. Tex Heart Inst J. 2001;28(4):322-323.

Authored by Dr. Michael Hohl and Dr. Ari Edelheit